Thursday, April 24

Who's Working for the Working Class?

Leo Mahe '26 and Eric Chen '27 (Opinions Associate) in Opinions | April 12, 2024

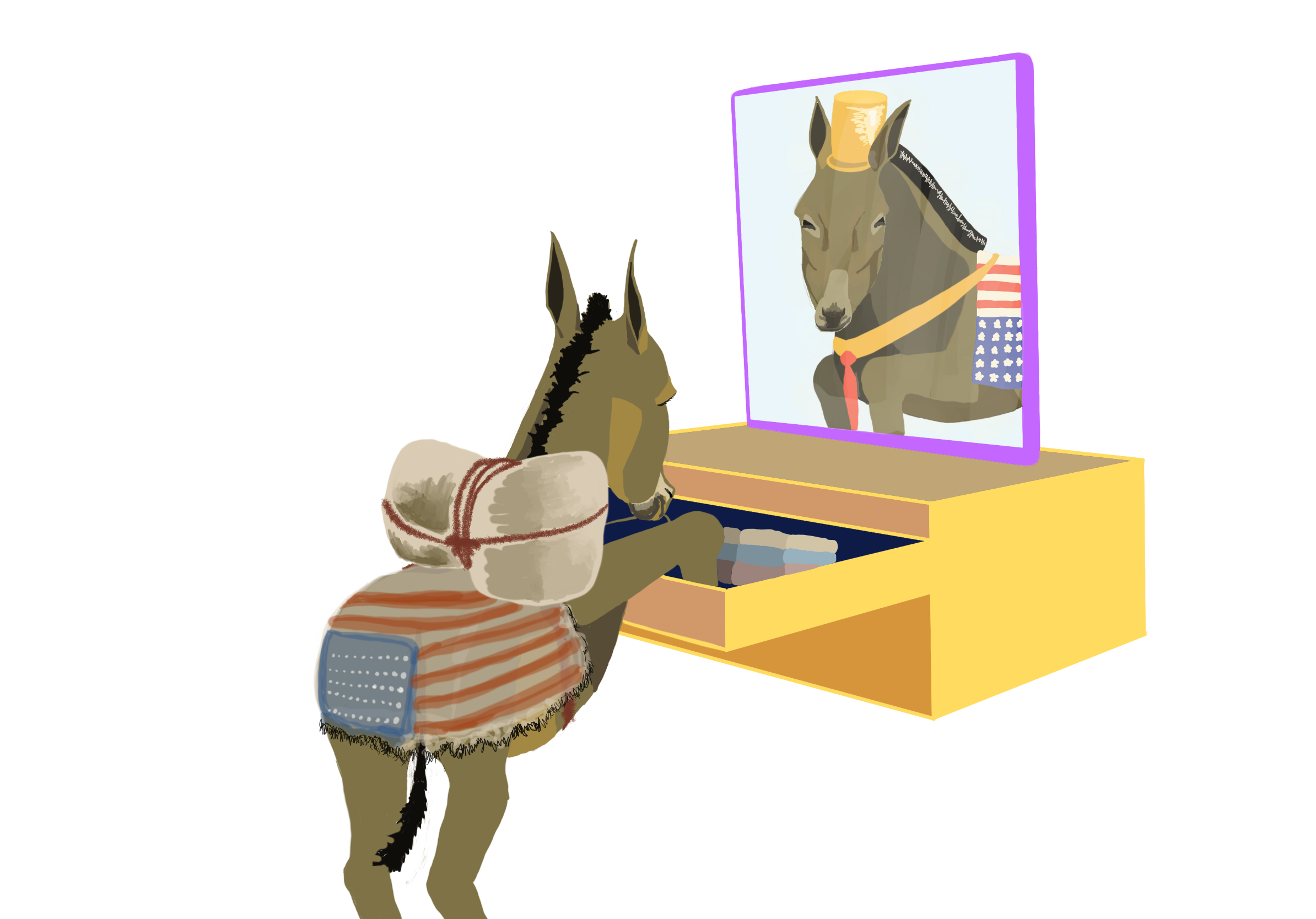

In a reverse-polarized political climate, where the electorate votes “against” candidates as much as they vote “for” their rivals, Trump should be a pretty easy target, right? The fascist rhetoric, his history of sexual assault, 88 criminal charges. Yet, somehow, this cacophony of what would once have been an unelectable mess has become a winning formula for the presidency. The Democratic Party often expresses the incomprehensibility of Trump’s ascent to power; yet, like a narcissist wondering why they are disliked, the party has failed to look inward at their flaws.

The Democratic Party’s struggles with losing voters to Trump stem from its detachment from its traditional voter base: the working class. It wasn’t long ago that the Democratic Party was seen as the party of the working class. Yet, as David Horsey of The Seattle Times puts it, “The Republican Party, after a long history of unfailing support for plutocrats, has become the party favored by a majority of non-college-educated working-class voters and rural Americans.” Somehow, the Democratic Party’s core voter base has become more educated and wealthier, while the Republican Party has turned into the party of the working class, marking a complete shift from the politics of yesteryear.

In recent years, Democratic elections have relied heavily upon swing states predominantly located in the Rust Belt, a section of midwestern and northeastern America that is predominantly industrial and, most importantly, inhabited by the working class. According to Stephanie Ternulo of Time, “Whiter, less affluent communities in the industrial heartland of America—where residents are less likely to have a college degree—remain loyal to Donald Trump, seven years after they first helped deliver him the presidency.” In 2016, Trump was able to win Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin. In 2020, Biden was able to switch over all the aforementioned states except for Ohio.

The Republican Party, over the past few decades, began to threaten government shutdowns and government default, willing to take unprecedented measures. As this rebellious attitude brewed in the Republican Party, the Democratic Party continued its strategy of playing peacemaker, marking asymmetric polarization. Asymmetric polarization is the defining quality of modern-day American politics—while the right sinks further into radical politics, the left remains unchanged. This asymmetry shapes both parties’ policies and optics.

Amid rising anti-democratic sentiments in the Republican Party, a chaotic patchwork of state abortion laws, and a backlash against “woke policies,” the Democratic Party faces numerous roadblocks to enacting agendas increasingly isolated from popular will. These concerns should certainly compose a core part of their campaign, but more needs to be done on kitchen-table issues. Today, one can hear only murmurs of popular progressive policies, such as universal healthcare and a more aggressive wealth tax hidden in random tweets on Biden’s official Twitter account; he has called healthcare “a human right” and “not a privilege,” all while supporting a minimum tax of 25% for billionaires; these ideas were neither achieved nor have since become central to the Democratic Party’s platform. However, these are both overwhelmingly popular policies; according to a Reuters/Ipsos poll, 64% of Americans support raising taxes on the ultra-rich, and a Hill-HarrisX poll found that 69% of Americans support Medicare for All.

Democratic adoption of kitchen-table issues could be extremely beneficial to their broader campaign. As noted by Vox, in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, roughly 51,000, 47,000, and 116,000 voters, respectively, fled from supporting Bernie Sanders, a progressive candidate who campaigned on a wealth tax and Medicare For All, to voting for Donald Trump, someone diametrically opposed to Sanders. In the aforementioned states, Trump won 22,000, 10,000, and 44,000 votes, respectively. A study by the Cooperative Congressional Election Study found that in 2016, 12% of people who voted for Bernie Sanders ended up voting for Trump in the general election. Importantly, this was a group that did not support the Democrats on social issues, demonstrating that kitchen-table issues with progressivist, left-leaning ambitions can still lead to inroads with socially conservative voters.

In contrast, Trump’s advertising is simple yet powerful: give power back to the working class. He paints himself as a no-nonsense political newcomer, fresh and unbound from the shackles of wealthy interests. This was once the platform of Democrats like FDR, yet Republicans somehow managed to hijack it. Trump’s rhetoric on policy was entirely centered on the working class—he wants immigration reform to prevent the loss of American jobs, lower taxes to revitalize the economy, and support Big Oil to lower energy bills. Trump’s ability to understand what voters want and center his rhetoric around their desires is undeniable: He understands that radical populists like Marjorie Taylor Greene appeal to voters more than traditional policy wonks like Paul Ryan.

While Trump frames himself as a President for the working class, he has proven to be anything but; per the Economic Policy Institute, he enacted tax cuts that overwhelmingly favored the wealthy over the working class individual, weakened and even abandoned important regulations protecting worker’s pay, and stacked the Federal Reserve Board with candidates much friendlier with Wall Street than working-class individuals. These stances are hardly surprising; Trump, a billionaire, benefits far more from policies that improve the lives of wealthy individuals like himself than those that benefit the average worker.

And yet, he continues to hold onto the working class vote. He has a masterful ability to frame policies as beneficial to workers even when they’re not: He makes a corporate tax cut sound appealing to the working class, something the Democratic Party couldn’t do in their wildest of dreams. Trump, above everything else, is a brilliant salesperson and, thus, a brilliant politician in today’s day and age.

Trump’s victory should not have been surprising to the Democratic Party. Instead, it should have served as a warning—a warning that, eight years later, the party has yet to hear. The world is beginning to change, and with it, the political climate. The politics of today are radically different from the politics of years past—so much has happened in so little time. The route to victory for the Democratic Party is not one of stagnation but one of adaptation. Americans are no longer content with the establishment politics that seemingly fail to properly represent the people—voters are now more attuned to the inner workings of Washington than ever before and have realized who the politicians truly represent. Given this knowledge, they are suddenly less content with a Washington run by politicians with corporate interests and billionaires lobbying for them; politicians who are different will stand out.

There is no return to the old normal; instead, the Democratic Party must find fresh rhetoric and policy, committing to a campaign of genuine change centered on the working class. Like Trump, they must focus on the game of optics; Build Back Better in no way competes with Make America Great Again, and yet, in today’s political climate, Biden’s new slogans must. Biden, as well as the broader Democratic Party, must win based not on votes against Trump but instead on votes for himself. He must convince voters that, despite his advanced age and status as a political veteran, he is attuned to the politics of today. This is the arduous path awaiting Biden, and if the Democratic Party wishes to be greeted with the blue wave they so desperately want, this will likely also be the path they must take.

Related Articles

- Senior Reflection: Ellie Turchetta Ellie Turchetta ’25

- Letters from Dawes: A Vision for Advisory Shreshta Agrawal ’28

- Reflections on Wellness Week’s Hollow Promise Mira Ponnambalam ’26 and Shreshta Agrawal ’28

- Put Personality over Professionalization Sophie Liu ’27

- Letter to the Editor: "Fundatory" Events Changed My Brain Chemistry Sophie Liu ’27

Recent Articles

- Announcing: Valedictorian, Aurelian Speakers, and Faculty Speaker Sophie Liu ’27

- Senior Profile: Sophie Cheng ’25 Katherine Qiu ’27

- Debunking the Dining Hall Debate: Is Lawrenceville’s Dining Really That Bad? Isabelle Lee ’27

- Welcoming Our New VPs for 2025-2026 Sophie Liu ’27

- A Sweet Return: Melba Reopens with New Flavors and Community Spirit Ella Song ’27