Thursday, April 24

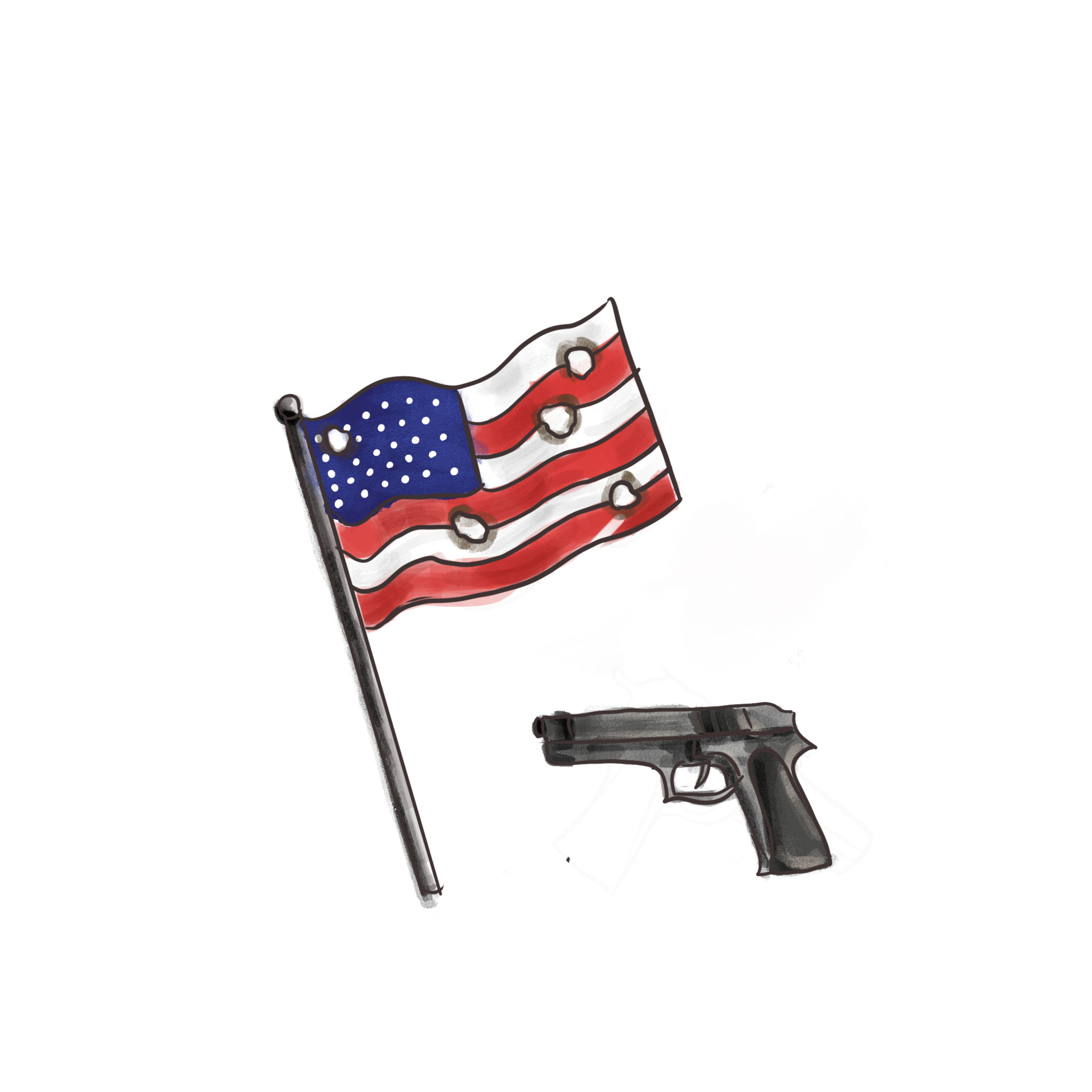

Don't Suffer Firearms and Fools Gladly

Sabrina Ottaway '25 (Opinions Editor, 144th Board) in Opinions | September 9, 2022

A mid-July Economist/YouGov poll found that six in 10 registered voters consider guns to be a “very important” issue in the upcoming elections. In response to these concerns, state governments have proposed conflicting laws concerning gun violence and the sale and distribution of guns. 27 Democrat states and the District of Columbia strengthened background checks and community intervention programs. Conversely, 19 Republican states unraveled restrictions on where and when to obtain and carry guns, like “permitless carry laws." The widening dichotomy of American responses to mass shootings reflects clashing assumptions over gun violence solutions. More specifically, these local communities’ clashes over the historical and cultural value of firearms greatly hinder America’s collective progress in eliminating our epidemic of gun violence.

As with almost everything, the history of guns in America begins with the U.S. Constitution. The widely-cited Second Amendment declares that a “well-regulated militia” is “necessary to the security of a free state” and asserts that “the right of the people to keep and bear arms…shall not be infringed.” Though this clause’s interpretation evolved over time, its original text designated a well-regulated militia as a tool for the state government to secure itself and its laws. In maintaining that the right to bear firearms was unalienable, the Constitution laid the groundwork for firearms to be associated with security, and the preservation of law.

The cultural value of firearms is also reinforced by mythologized teachings of local history. Take a look at my home state, Nevada. Firearms hold a dear place in my state’s history; residents’ long-standing reliance on firearms along with the lore of revered historical figures’ heroism with guns have ensured the social importance of firearms. I remember lessons at school on Kit Carson. A U.S. Army agent, wilderness guide, and propeller of Western expansion; stories of Carson’s immense bravery, leadership, and self-sufficiency created a narrative of reverence. In the many statues I saw of him around Carson City, Nevada’s capital, Carson usually brandishes a rifle; sometimes, he rides valiantly on horseback. When we memorialize figures like Carsons through our history books, statues, and cities, we feed into the American narrative of a “good man with a gun.” Eventually, and inevitably, the rifle becomes practically synonymous with all the values said historical figures championed: power, safety, and security.

But these historical ideals also spill into the present. In the past two years, I attended rallies supporting Democratic leaders around Northern Nevada. Some attendees chose to brandish written signs conveying their political values, while others would visibly showcase their firearms to convey their opinions. Of course, Nevadan conservatives have always been quick to claim the mythological equivalence of gun ownership with power, security, and local heritage for their own. For example, in rural areas, guns are often lauded as a security measure against bears and mountain lions.

But the practical use of these weapons has become a way to justify their use as a political weapon. This phenomenon is far from limited to Nevada. Across the nation, politicians and officials wield the firearm’s cultural symbolism in their respective town, district or state as the basis for solving mass shootings. After the 2012 Sandy Hook shooting reignited the national debate on school shootings, a spokesman for the National Rifle Association (NRA) notoriously claimed that “the only way to stop a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.” This logic has become a popular saying among conservative pro-gun politicians and pundits, and with sound reason: this saying articulates the security and safety Americans feel towards the positive symbolism of the armed police officer and the protective militiaman.

Such logic then translates into legislation. Six majority-Republican states have repealed requirements for background checks and permits to carry concealed and loaded weapons in public spaces. Montana passed a law allowing guns in K-12 schools and on university campuses. Ohio passed a bill allowing teachers to be armed in the classroom. Supporters of these bills argue that loosening gun regulations ensures that there will always be a “good guy with a gun” when people are in danger.

But laws that reinforce the firearm’s cultural value fail to actually ensure a decrease in mass shootings. We’ve seen the disproving of this “good guy with a gun” argument at the Uvalde, Texas shooting in May. Despite the deployment of 376 law enforcement officers to the school, a State House panel concluded the law enforcement response was plagued by "systemic failures, egregious poor decision making, and a leadership void.” The result of this inefficient law enforcement was the third deadliest school shooting in American history. While there is not an immense volume of research on school shootings, an Everytown study confirmed the explicit correlation between weaker and more lenient gun laws, and a higher rate of gun deaths, including homicides.

But even these statistics aren’t enough for many states. While politicians across the country face pressure to provide gun violence solutions, they are often expected to avoid solutions that conflict with Americans’ ingrained perceptions about guns and those who carry them. To put it bluntly, the cultural significance of guns stymies political progress that should have been accomplished long ago. As a result, attempts at productive discourse and solution-building surrounding “culture” and “values” in a country staunchly divided on gun control fall flat.

Still, there remains hope. If Americans were to scrutinize and implement gun policies based on how well they fare in studies, the benchmark for action would be based on research and facts. Accepting that the benchmark should be founded upon objectivity rather than nostalgia and romanticization will be difficult, but is a necessary step that more Americans and politicians must agree to. Shifting the crux of the gun control discussion from Constitution-era ideological values to modern research and statistics will require the American deconstruction of mythical notions that surround guns. It is the only way to ensure that we can produce popular solutions successful in preventing gun violence.

If we rely more on research in political discourses on how to solve gun violence, our solutions will be more efficacious and attract the support needed to survive the democratic process. Finally, there’s a clear plan for moving forward: funding more causality-based research in gun violence and evaluating possible solutions to gun violence already implemented in some states. We must establish a national plan founded upon a common ground of American commitment to rid gun violence to solve our mass shooting problem. We have seen too many times how ignoring our biases and preconceived notion about guns impedes our ability to pass preventative gun violence laws. As our political environment grows even more ideologically polarized, implementing these laws will only get harder. We simply cannot wait any longer.

Related Articles

- Senior Reflection: Ellie Turchetta Ellie Turchetta ’25

- Letters from Dawes: A Vision for Advisory Shreshta Agrawal ’28

- Reflections on Wellness Week’s Hollow Promise Mira Ponnambalam ’26 and Shreshta Agrawal ’28

- Put Personality over Professionalization Sophie Liu ’27

- Letter to the Editor: "Fundatory" Events Changed My Brain Chemistry Sophie Liu ’27

Recent Articles

- Announcing: Valedictorian, Aurelian Speakers, and Faculty Speaker Sophie Liu ’27

- Senior Profile: Sophie Cheng ’25 Katherine Qiu ’27

- Debunking the Dining Hall Debate: Is Lawrenceville’s Dining Really That Bad? Isabelle Lee ’27

- Welcoming Our New VPs for 2025-2026 Sophie Liu ’27

- A Sweet Return: Melba Reopens with New Flavors and Community Spirit Ella Song ’27