Thursday, April 24

Interim Interventions: How Revised Responses Promote Performativity Over Reflection

Arya Vishwakarma '25 (Opinions Editor, 144th Board) in Opinions | April 28, 2023

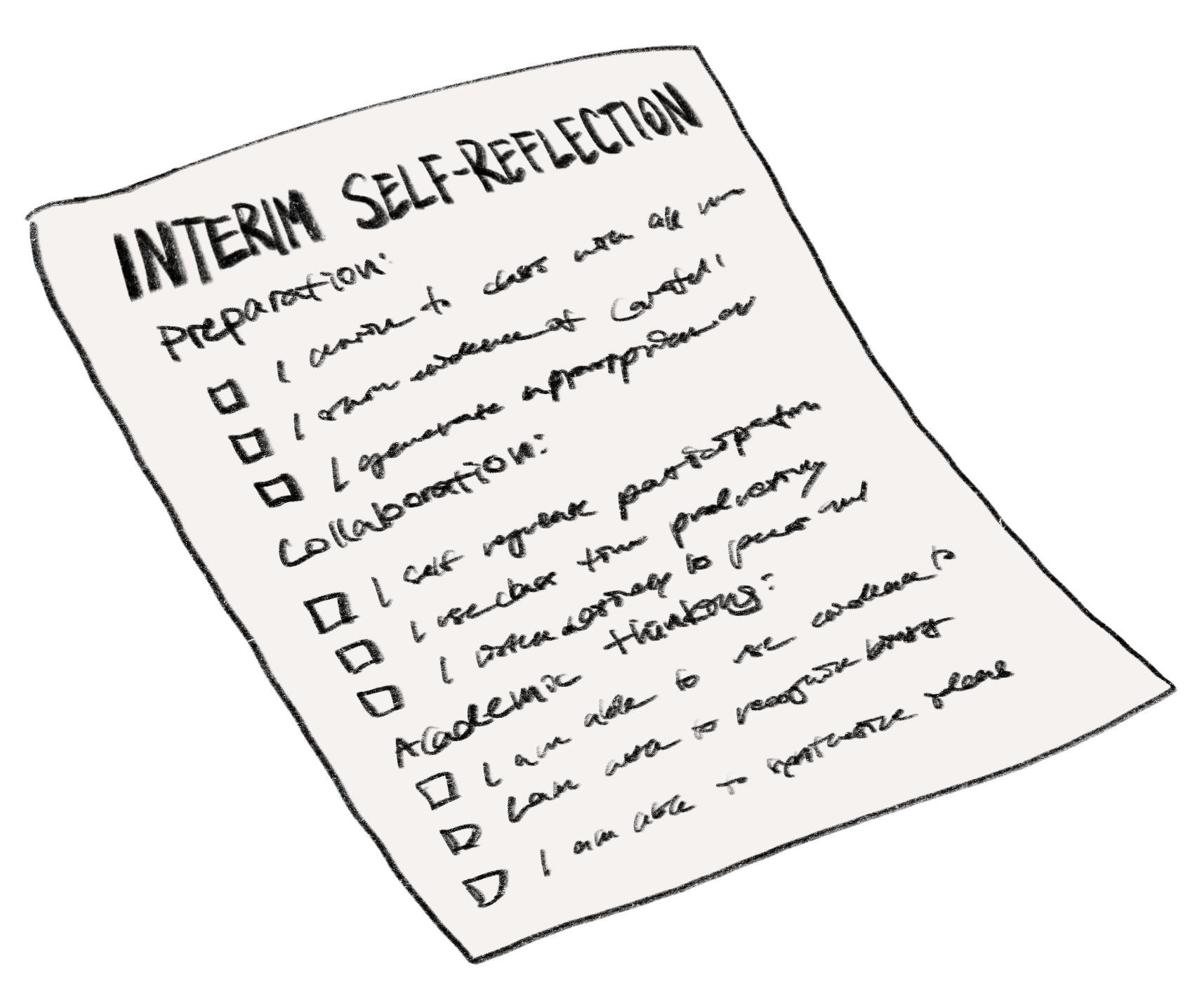

With interim comments coming out earlier this week, Lawrentians are reckoning both with how to respond to the last written feedback from their teachers each term and the new format this advice has been presented in. In an effort to increase transparency between students and teachers, the comments have taken on a new format this year. Instead of just receiving comments from their teachers, this term students were asked to fill out a Google form assessing their own performance in the class. The responses from these forms essentially served as outlines used by teachers to then frame students’ interim comments. Interims, in theory, are meant to bridge the long gaps of time between final comments and provide advice that students have time to implement before finals week. They are valuable because they are personalized—teachers are trained to give students advice that lets us reach our learning goals most efficiently. Our personal growth results from our reactions to this impressively frequent feedback: six written comments a year per class is far above the amount most schools deem necessary for their students.

Our teachers work hard —this weekend and Scheduling Day many typed comments late into the night after the usual slew of grading and advising. Ideally, we should all support proposals that make their lives easier and more efficient. However, the new interim process is not as streamlined as it appears, with thoughtful responses to the forms requiring wading through each multiple-choice and short answer. I won’t speak for teachers’ workloads, but I do believe that examining an interminable list of hastily-composed reflection forms is unfair for us to ask them to do, because it could easily become repetitive and monotonous. Time they spend filing through responses is time that could be better spent writing thoughtful and helpful comments based on their already extensive knowledge of their students’ habits, which is important because interims exist solely for our benefit in the first place. An ideal system would consider the needs of students as a first priority and give teachers time to write, but the revised format has not improved at either of these goals.

The purpose of the forms this term was to increase greater transparency between a student’s reflection of their own performance and their teacher’s perception of them; students who spent more effort on these forms (often assigned for a short 10 minutes during a class period) could receive more relevant comments. In theory, there is value in engaging in thoughtful criticism of ourselves and taking charge of our own learning—the middle of the term is a great time to do that. What’s ignored in this revised interim-writing process is that self-reflection takes time and discipline—we need to be honest with ourselves and treat growth as an ongoing journey.

A check-box form for every class is not a replacement for that experience. Filling one out knowing that our teachers will be viewing our written responses and putting it in a report may incline some to change the tone of the reflections from honest and thoughtful to artificially humble and syrupy sweet. In some of my own comments, I received quotations from teachers such as “the goals you’ve set for yourself sound good,” leaving me with no feasible strategies to improve recommended by my teachers. I think it’s important that my teachers and I agree on my perception of how I’m doing in class, but this online self assessment was not as accurate in tone and content as a face-to-face meeting would have been. Without room for real, constructive self-criticism to be discussed between students and teachers, interims essentially become performative.

What if we started the conversation about student growth earlier and more consistently, similarly to the weekly advisory process? What if consultation (on the rare, regular-schedule days that we have it) was used as a place to check in on progress more often? Most importantly, what if we remembered to incorporate more human connection into our journeys of learning and growth by normalizing open communication with our teachers about the inevitable hills and valleys on the rollercoaster of academic pursuit? I believe that we are capable of more effective strategy than simply avowing to come to consult more often or highlight our nightly readings with more colors. A better interim process that’s more conducive to real self-reflection has the potential to finally serve as the best option for all of us.

Related Articles

- Senior Reflection: Ellie Turchetta Ellie Turchetta ’25

- Letters from Dawes: A Vision for Advisory Shreshta Agrawal ’28

- Reflections on Wellness Week’s Hollow Promise Mira Ponnambalam ’26 and Shreshta Agrawal ’28

- Put Personality over Professionalization Sophie Liu ’27

- Letter to the Editor: "Fundatory" Events Changed My Brain Chemistry Sophie Liu ’27

Recent Articles

- Announcing: Valedictorian, Aurelian Speakers, and Faculty Speaker Sophie Liu ’27

- Senior Profile: Sophie Cheng ’25 Katherine Qiu ’27

- Debunking the Dining Hall Debate: Is Lawrenceville’s Dining Really That Bad? Isabelle Lee ’27

- Welcoming Our New VPs for 2025-2026 Sophie Liu ’27

- A Sweet Return: Melba Reopens with New Flavors and Community Spirit Ella Song ’27