Friday, April 19

Dear God, It's Really Not Your Place

Lauren Liu ’24 in Opinions | September 16, 2022

God is not a fact. So I’ve always wondered: if we aren’t able to verify the existence of God, why is God always right? Are what we believe to be God’s claims truly objective? How and why do we so fervently trust something we’ve only imagined?

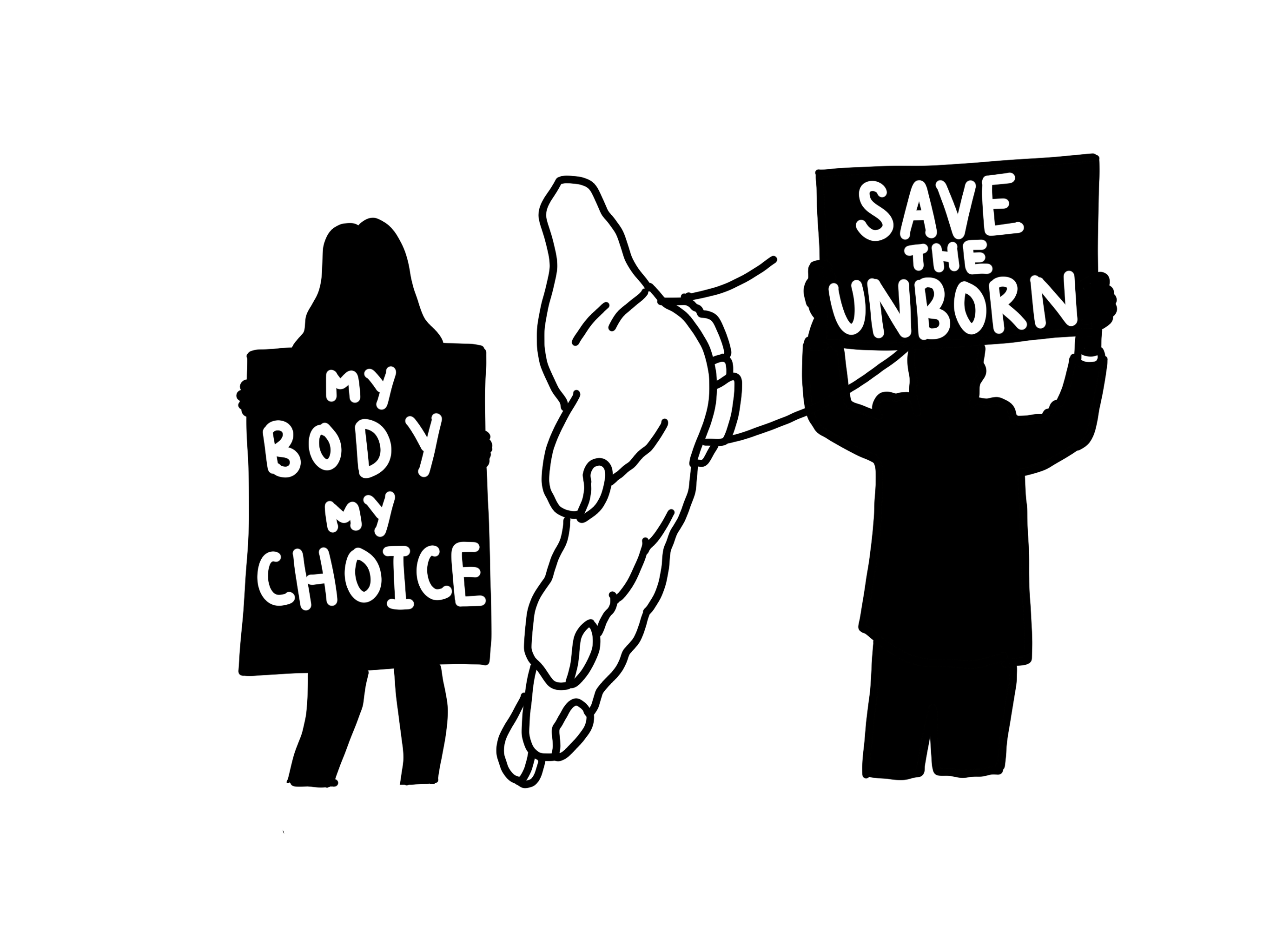

Religion manifests itself in every aspect of American life. In the classroom, the pledge of allegiance famously unifies America as “one nation, under God.” In American literature, authors use Biblical allusions to enrich their stories. And for better or worse, religion is frequently utilized as a means for political debate. For better: Americans’ dissatisfaction with the long-lasting power imbalance between white and black people intertwined with Christian ideals to empower the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. For worse: religion paved a large portion of the road to Dobbs v. Jackson, the case in which the Supreme Court ruled the right to abortion to be unconstitutional. This recent overturning of Roe v. Wade triggered widespread anxiety and controversy over its anti-feminism implications, and for good reason. Following Dobbs, at least 12 states have made abortion illegal. In the future, approximately half of all U.S. states are expected to enact bans.

One of the central tenets of the pro-life argument is God’s belief that abortion is sinful. But whether or not you agree with that statement should not matter in the abortion debate. Using religious beliefs as an argument only strips moral responsibility away from individuals. To put it bluntly, citing God is just the easy way out. After all, the matter of fact is no human being, even the Pope, will ever know what God truly wants.

By no means am I insinuating that religion is intrinsically harmful and corruptive, nor am I ridiculing those who believe in God. While I am not the most active participant in church, I am still a Christian. Growing up, my parents would reiterate “everything is God’s best plan,” the lesson of a renowned Chinese fable, ad nauseam. But the validity of Christianity in our personal lives does not equate to the validity of Christianity in political arguments.

Still, the use of religion to justify political and social immoralities is far from a novel occurrence. The Transatlantic Slave Trade of the 16th century is a prime example. To justify their transport of approximately 12.4 million people to labor on plantations, European nations deliberately misinterpreted the Bible to wield Christianity as a pretext for enforcing absolute authority over Africans. Through missionary efforts, coupled with threats of starvation and torture, these same nations sought to refine African culture, or to force Africans to convert from their ‘low-level’ religions to the ‘intrinsically superior’ Christianity.

It’s not all too surprising that religion has been a major participant in the abortion debate since it first arose. Though abortion was regularly practiced in ancient civilizations, its legality has continuously been disputed in the modern ages. In 1588, Pope Sixtus V declared all abortion murder, holding the belief that ensoulement––the moment at which the soul enters the body––begins at contraception, establishing one of the key points of contention in abortion rights over four centuries later. In the 21st century, we need only a quick statistical study to confirm the close relationship between religious affiliation and political stance on abortion. Take a look at a recent Pew Research Center study: 79 percent of adults who support the illegalization of abortion believe in God.

American ideological fervor is only growing stronger, and at a considerably alarming rate. What was once religious belief has now turned into political belief. The separation of church and state—one of the founding values of the United States—has dwindled down to almost nothing. Although both religion and politics govern our moral code, we cannot conflate the two.

This conflation only empties religion of its meaning; it not only enforces subjective religious standards upon non-practitioners, but sullies religion’s purpose to promote love and respect for all individuals. Citing the abstract notion of God in a debate on concrete matters like abortion brings all productive discussion to a standstill. No one has the grounds to prove or disprove the existence of someone’s God, and thus we have nothing to debate about.

When will we accept that the separation of church and state is not an option to occasionally consider, but an American requirement? When will we accept that opinions formed from facts, not from mere conjectures, are integral to political progress?

Thus, forgive me, God, but I don’t love you in politics. Interpretations of the Bible are ever-changing. Inconstant. Unstable. If religion, a fickle and multi-faceted system, is used for political purposes, what ensues is nothing but a vicious cycle of shallow political machines vying for power.

Let’s try to avoid that.

Related Articles

- Senior Reflection Sneha Kumar ’24

- Senior Reflection Bryce Langdon ’24

- Senior Reflection Christopher Yen ’24

- Senior Reflection Sofia Bonilla ’25

- The War on Thinking: Censorship in Curriculums Sarah Jang ’27

Recent Articles

- Leading the Boat with the Teeleys Celestine Sutter ’27

- Earthquake Strikes Campus Mia Kincade ’25

- Artificial Justice For All

- From Passion to Action: Behind the Scenes of LCAPs Mira Ponnambalam ’26

- Eli Lacey '25: Let's Drive it Home Sienna Soemitro ’26