Wednesday, April 24

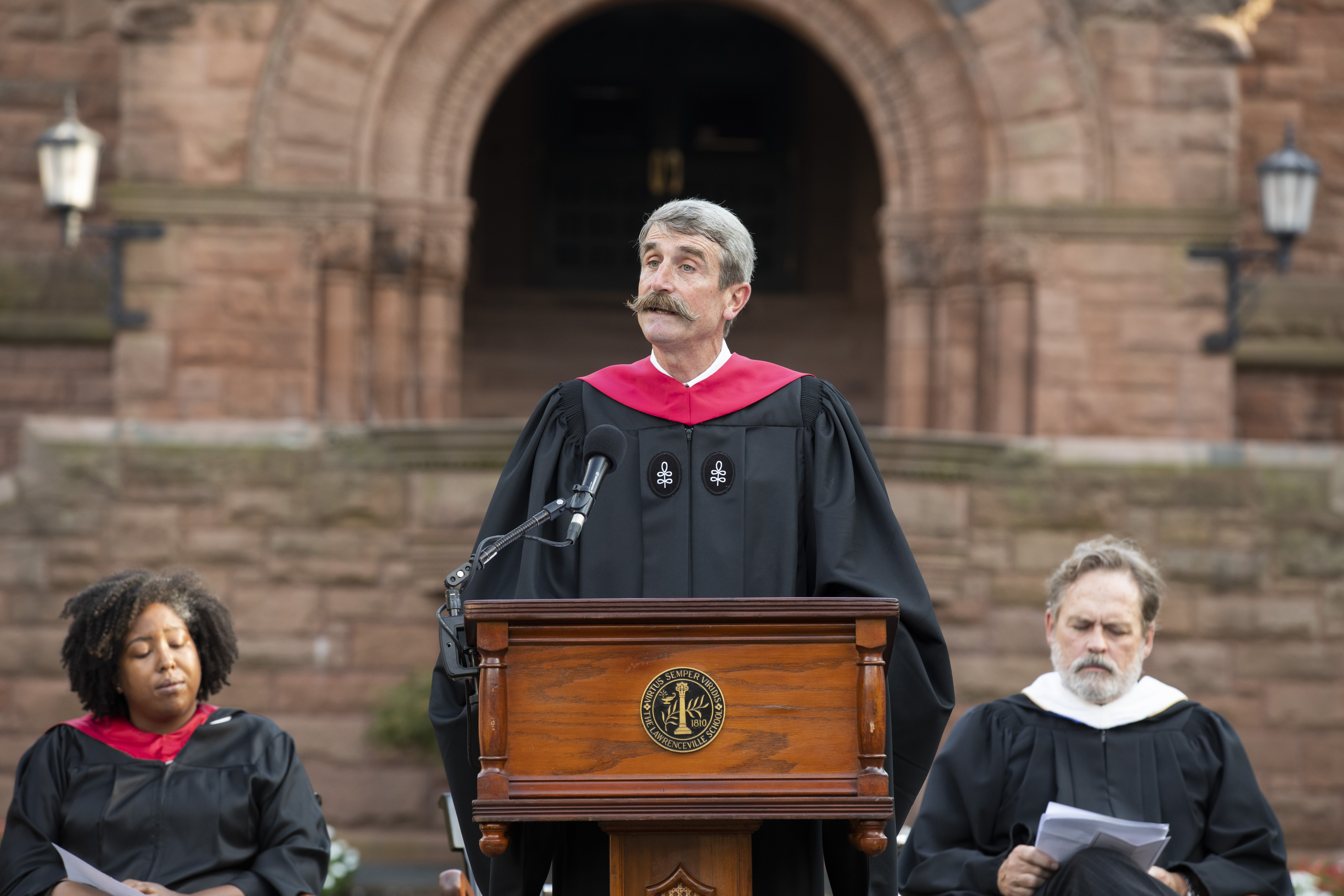

Murray Delivers Speech "On Faith"

Stephen Murray (Head of School) in News | September 9, 2022

One gray morning on the outskirts of the town of Killarney, in County Kerry, Ireland, as I stood by the side of the road with my thumb out, the skies opened up, and I was quickly soaked to the skin by a passing shower.

I was 20 years old and hitchhiking by myself through the British Isles. I could only afford a Bed and Breakfast about every 3rd night, and in between nights under a roof, I’d sleep out in cow fields or behind hedges. I sustained myself primarily on tea, Irish soda bread, local cheddar cheese, and in the evening, a pint or two of Guinness.

After my drenching that morning, the sun eventually came out, and dried me slightly, but I was looking, and feeling, like a drowned rat, and wasn’t sure anyone would dare pick me up. But this was Ireland in the 1980’s, where people still had a bit of faith and trust, and I was getting used to the fact that even little old ladies would stop for a scruffy, unshaven hitchhiker like me.

Sure enough, in spite of my appearance, a car pulled over before long. The driver introduced himself as Frank Hickey, and said he’d be happy to take me as far as Skibbereen, a small coastal village where he was headed.

Our route took us along the beautiful Ring of Kerry, with its rolling green hills, ancient stone walls, and dense thickets of purple rhododendron in full bloom. He was chatty and personable, and I learned quite a bit about him as we drove: He was university educated, well traveled, and cosmopolitan; he had studied choreography and was passionate about classical music, especially Brahms, which played in the background as we drove; and he had survived a serious bout of throat cancer through a remarkable surgical intervention.

Suddenly, without explanation, he pulled off the road and headed down a narrow, overgrown, dirt track. In response to my sidelong glance, he said, “I just have to do a quick side errand, it won’t take long.” As we drove out of sight of the main road, in the middle of nowhere, it occurred to me that I had just met this guy, and a slightly uneasy feeling crept into the back of my mind.

After bouncing along the uneven, deserted trail for some time, we pulled up to a forlorn-looking graveyard dominated by mossy, stone Celtic crosses poking up out of the tall grass.

He told me that he was looking for the grave of a woman, and further explained that according to local lore, she had died quite young, over 50 years ago, and he added, “still a virgin.” Apparently, thirty years later, they dug up her plot to bury her brother, who had died, and they found her coffin and her body, in Frank’s words, “perfectly preserved,” as if no time had passed at all.

When we found the grave, it was covered with small offerings and tributes – clearly others had also made this pilgrimage.

According to Frank, she was an unofficial local saint, and folks in the area had an almost mystical regard for the story. As he said this, he took a handful of earth from the top of her grave and put it in a small bag. “I have a friend dying of cancer,” he said, and then added earnestly, “I am going to put this under his bed. He is in tough shape, and I want to make sure we try everything.”

Later that day, after a Guinness at a local pub, he dropped me off on a beautiful stretch of rocky coast overlooking the North Atlantic, where I swam, dined on Irish soda bread and cheese, and then watched the seals and cormorants as the sun finally went down over the ocean, about 10:00 pm on that late, northerly, June evening.

As the light faded, I thought back on that moment in the graveyard earlier – here was a worldly, highly-educated individual who had significant, personal experience with the medical establishment, and who, at the same time, in almost contradictory fashion, placed great store in what appeared to be local folklore.

As I reflected, it occurred to me that many would dismiss his belief as mere superstition, but the more I thought about it, I preferred to call it a kind of faith – faith that there is wonder in the world beyond our understanding, an acceptance that there are currents at work that we simply can’t explain, that are beyond our ken. Indeed, aren’t our lives reduced to more of a soulless transaction with the physical world if we don’t accept, if we don’t have faith, that there is just a bit of magic out there?

Part of what makes us all human are the various ways in which we bring faith into our lives, ways in which we trust in things we can’t fully explain or fathom. And this faith takes many forms.

There is of course religious faith. 17th century French philosopher and theologian Blaise Pascal wrote extensively on the nature of faith and belief. In his major work, Pensées, or Thoughts, he echoes this notion that faith nurtures in us a sense of awe and wonder.

“Faith tells us what our senses cannot,” he writes, meaning that faith is not limited by what we can see and perceive, quite the contrary – faith begins where perception ends.

He goes on to say, “It is incumbent upon our power of reason – our rational faculties -- to recognize that there are infinite aspects of our existence that go above and beyond our understanding.” In other words, if everything must pass the test of rational scrutiny in order for us to believe, we lose our sense of mystery in the world.

Regarding faith in God, he reflects, “God either is … or isn’t,” and though a mathematician and scientist, he concedes that no amount of human calculus can determine which one of those propositions is true. But nor is it a simple coin toss to decide which to believe – that is not a wager worth taking. Choose the former, he cautions -- that God exists. If it turns out not to be the case, you lose nothing; if, however, you find God there to greet you at the gates of Heaven, your faith will surely help you gain entry, thereby avoiding the unpleasant alternative.

Professions of faith also can be looked at from a linguistic perspective. One’s own assertion of faith, as Harvard philosopher Israel Scheffler argues, carries a connotation of certainty. So, for example, a very observant practitioner of a particular religion might say, “I have lived such a pious life, I know I will be rewarded in the afterlife by my God” – even though that is of course a leap of faith.

By the same token, when one ascribes “believing” to another, as opposed to “knowing,” it suggests disagreement – as in, “Medieval peasants believed that disease was caused by evil spirits, though I happen to know that viruses are the cause.”

Of course, even here, some would argue that scientific explanations themselves can amount to a ‘leap of faith.’

If we drop a bowling ball from a building 1000 times and it falls at a consistent rate, we decide that the behavior of the object is governed by a universal, immutable law. Still, a skeptic might ask, “On the one thousand and first try, might the bowling ball might fall at a different rate, or not fall at all?” From Aristotle’s deductive theory of gravity to our modern, inductive approach, think of how often and how dramatically our basic understanding of the workings of the universe has changed over time. We can still choose to say we know the bowling ball will fall – but to some, it’s a leap of faith.

In this regard, science and faith are not necessarily incompatible, and just as I found with Frank Hickey in that graveyard so many years ago, they sometimes go hand in hand. While physicists tell us there is much we can grasp about the universe, this scientific perspective does not rule out the mysteries and wonder of our existence. Albert Einstein saw a beautiful correlation between what is knowable in the universe and what may be beyond our grasp. MIT professor Eugene Mallove wrote, “Einstein had faith that, ‘God is subtle, but he is not malicious.’ By this he meant that even though the Universe did not reveal its inner workings easily, it would not torture us with impossibly devious riddles.”

In other words, Einstein saw the world as “strikingly regulated,” and therefore all the more awe inspiring. Glimpsing elements of a rule-governed universe only increased his faith that mysteries lie beyond. The rules belong to science, but for Einstein, like Pascal, the limits of human understanding heightened his sense of wonder: “Science without religion is lame,” he wrote, and “religion without science is blind."

There are still altogether other forms of faith, forms that have a more human dimension. A number of years ago I was traveling through South Africa, and I visited the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg, an extraordinarily powerful exposition of the human capacity for cruelty and injustice.

Later that day, I was back at my hotel sitting in the locker room of the fitness center, still absorbed in thought from my visit to the museum. Two burly, blond men speaking Afrikaans were also changing, chatting quietly. Then a Black man entered the room to change for a workout – and nothing happened. Nothing at all. I thought to myself, just 12 years earlier, the law of that land institutionalized racism, enforced segregation, and subjected this Black African to humiliating degradation. And here he is, walking casually into a fully integrated locker room, and no one bats an eye.

How had this country moved so far in such a short period of time? In our own country, the United States of America, 12 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, the Ku Klux Klan was on the rise, Jim Crow laws were proliferating, and it would take 100 years to pass the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, and only then after bitter struggles.

To be clear, post-Apartheid South Africa saw plenty of violence, as Trevor Noah writes in his autobiography, Born a Crime. And yet, given the history of our own country, I still marveled at the simple scene I was witnessing in a society that had so recently emerged from pervasive, state-sponsored, systemic racism. How had they accomplished this?

In part, I believe it was the faith of Nelson Mandela.

One of the great leaders of the 20th Century, Mandela endured 27 years of soul-crushing imprisonment for daring to fight for equality and the end of Apartheid. He survived by holding on to what he referred to as his fundamental optimism: “There were many dark moments when my faith in humanity was sorely tested, but I would not and could not give myself up to despair. That way lays defeat and death.”

In spite of his suffering on Robben Island, he maintained his belief that people could come together, his faith that people could change. “No one is born hating another person because of the colour of his skin, his background, or his religion,” he wrote. “People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.”

He knew they would not always get it right, but he also knew that if each person trusted in the good will of the other, they had a chance. Given the conditions that Black members of that society had so long endured, there could have been Civil War, but Nelson Mandela had faith in people.

When he emerged from prison and rose to power, he asked his fellow South Africans to forgive each other: “You will achieve more in this world through acts of mercy than you will through acts of retribution.” Mandela’s faith saved lives and preserved his country.

As for me, I maintain a faith that has many of the dimensions I have described: a belief that there is mystery and magic in our world beyond our understanding; that science and religion don’t have to be mutually exclusive, if one can set aside dogma; and that leadership based on compassion and empathy can prevail against cynicism and brute force.

But what I rely on most is even more promising and hopeful for me. I have faith in you. All of you.

I referenced this briefly the other night in our opening School Meeting. As we kick off a new year, your arrival has breathed life back into this campus; you are at the heart of this rejuvenating cycle that we all have the privilege of being a part of. But it is not simply youthful joy and energy. What inspires my awe and respect is your ability to emerge out of the challenges of recent years, to have faced sacrifice and disappointment, as you all have, and still muster the kind of hopeful, forwarding-looking passion I have seen and sensed so clearly these past few days: I saw it at preseason; I saw in the warm welcome given to our new students; I saw it in School Meeting last Wednesday; and I saw it yesterday at House Olympics.

And you know well the challenges and sacrifices to which I refer.

You have experienced the prolonged, sometimes bitter focus on racial injustice prompted by the death of George Floyd. While we have had moments of solidarity, many factions remain entrenched and hopelessly at odds.

Since the spring of 2020, in one form or another, you have known lonely periods of remote learning; mask mandates; weekly PCR testing; closed common rooms; and cancelled athletic seasons.

In the early days of the pandemic, during those initial bewildering weeks of March 2020, when we hunkered down in self-imposed, fearful isolation, my older daughter Maggie wrote in her journal, “Day 13 of the pandemic, not sure how much more of this I can take.” If only we knew then what lay ahead, and yet, you all persisted.

Sometimes simply getting out of bed in the morning to face the day, even with the anxiety and dread you likely felt at times, is an act of faith and courage. And you did it over and over, and found strength you didn’t know you had.

And I speak especially to you Vth Formers, as we rely on you to provide leadership this year – you will set the tone, you will set the example. I think especially of you when I refer to challenges that have been endured, and yet here you are, already out front, already showing us the way. For all of the obstacles you have encountered directly in your path, you are wiser, more thoughtful, more appreciative of the opportunity of being here, and this is precisely why you are so well equipped to lead the School this year, and why I have such faith in the year that lies before of us.

So indeed, faith comes in many forms. Frank Hickey found comfort and solace in a local legend – and held out hope for a miracle. For Albert Einstein, science enhanced his profound appreciation of the mysteries that lie beyond, mysteries more in the realm of religion.

Nelson Mandela taught the world that human beings can set aside the hatreds they have learned, and change for the better.

And as I look out at all of you here today, you give me tremendous faith, not simply that a great year lies ahead, but that you will take with you out into the world your resilience, your hard-earned wisdom, your belief in yourselves, and put it all to work in wonderful ways. And this is the faith that sustains me most.

So find the faith that sustains you – it is truly a gift – and hold it close.

Thank you very much, and let’s have a great year.

Stephen S. Murray H'54 ’55 ’65 '16 P’16 '21

The Shelby Cullom Davis '26 Head of School

Related Articles

- Discovery Days 2024 Angel Xin ’26

- Community Iftar in the Bathhouse Ethan Zhu ’26

- Earthquake Strikes Campus Mia Kincade ’25

- Eli Lacey '25: Let's Drive it Home Sienna Soemitro ’26

- Emily Pan '24 Named Valedictorian Staff Report

Recent Articles

- Concerts, Plays, and All That Jazz: An Update on Spring Productions Jane Shindnes ’26

- How the Need to “Know Ball” Is Destroying Sports Discourse Bryan Boanoh ’25

- Out With the New, In with the Old: What Makes a Gripping Period Piece? Celestine Sutter ’27

- Singing into Spring: A Spring Playlist Riley McKibben ’25

- Senior Profile: Garrett Heffern '24 Angel Xin ’26